New Gift for Soybean Farmers

Delivering solutions quickly to transform a vital crop.

Anew gift is on the way for the world’s soybean farmers: varieties with better disease resistance than ever before.

Soybeans are an essential crop for the global food system. Good for nitrogen fixation in soil and a useful cash crop, soybeans are the second most popular vegetable oil in the world, and a staple part of the diet for hundreds of millions of people.

However, like so many of the foods that we depend on, soybeans are under constant threat from disease. And this threat shouldn’t be underestimated. Take Asian Soybean Rust (ASR), for example. It can ruin whole fields of soybeans, costing farmers up to 80 percent of their harvest.

Qiudeng Que, Head Research Pipeline Enablement at Syngenta, says: “ASR is a two billion dollar a year problem just in Brazil.”

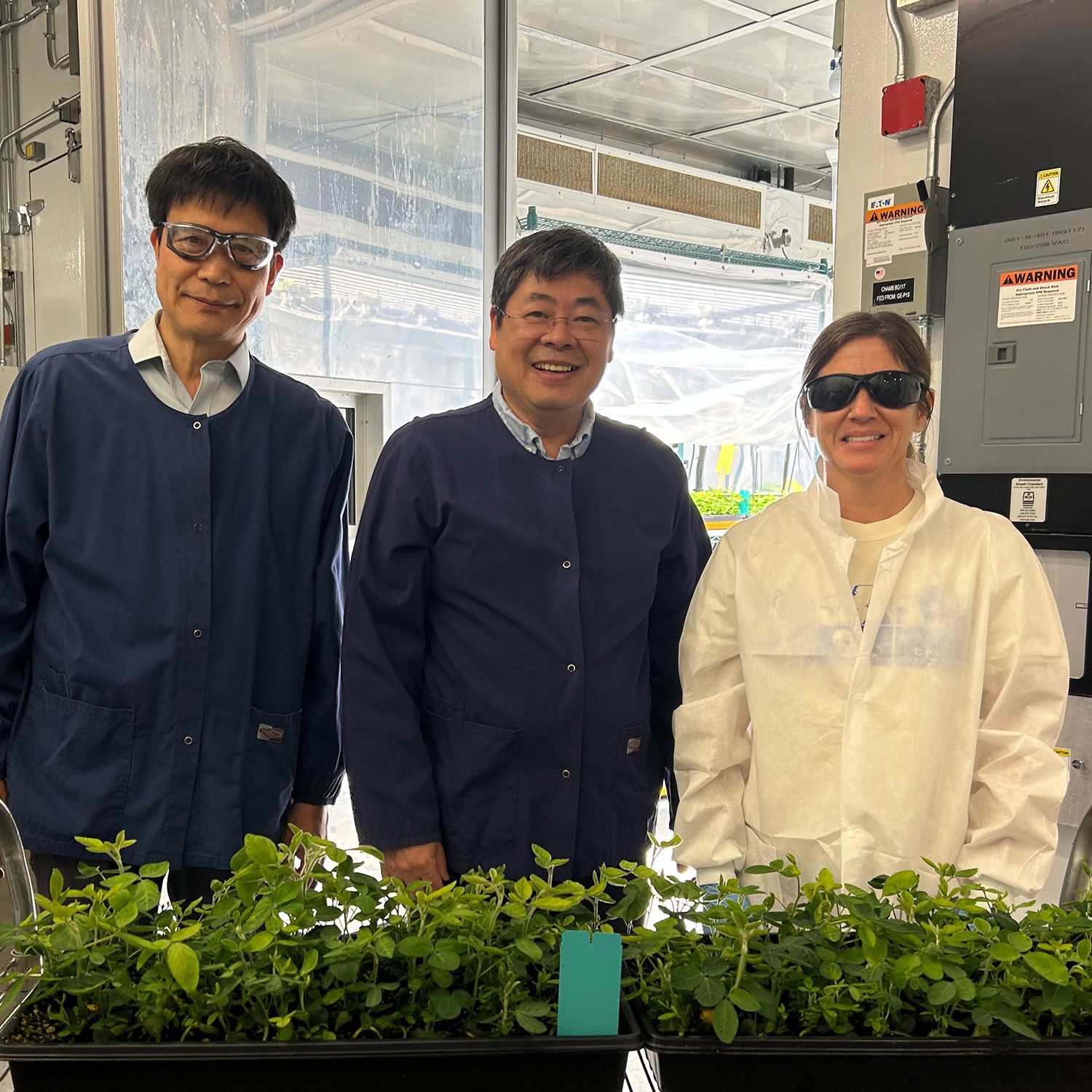

The GiFT team (from left to right): Tara Liebler, Heng Zhong, Rebecca Flanagan, Changbao Li and Qiudeng Que.

The GiFT team (from left to right): Tara Liebler, Heng Zhong, Rebecca Flanagan, Changbao Li and Qiudeng Que.

Tackling the problem

Rampant disease is a perennial problem for farmers. When a cloud of fungal spores descends on a green field, lesions and pustules appear on leaves and stems. Unchecked, ASR has a catastrophic impact on yields, often destroying entire plants.

To eradicate ASR, farmers apply fungicides. Rather than depend on this, it makes more sense to protect the plant at a much earlier stage by breeding crops with genetic immunity. But how is this achieved?

Since the days of Gregor Mendel, the father of modern genetics, traditional breeding has involved crossing one plant with another. In this way, a new generation is produced that expresses a desirable genetic trait.

If you can find a soybean plant with genetic immunity to a disease like ASR, you can take it to the next level and breed a hybrid line that carries that immunity.

While this practice still goes on, the drawback is obvious: traditional breeding takes a lot of time, especially when breeding with wild species that carry immunity genes. When diseases move and evolve, a plant’s immunity can quickly fail.

In addition, high-performing soybean crops generally don’t have wide genetic variability. So, it’s likely that if one top performing soybean line isn’t immune, then others won’t carry immunity either.

Que says: “Think of them as a very closely related family.”

To reduce dependency on applying fungicides, this new breakthrough would protect the plant at a much earlier stage.

To reduce dependency on applying fungicides, this new breakthrough would protect the plant at a much earlier stage.

Gregor Mendel, photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Gregor Mendel, photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

The breakthrough

And so, over the past 30 years, researchers have worked hard on genetic modification (GM).

“This means taking a gene from a different plant - or another source - that carries immunity, placing it into your target, transforming it into a carrier of this new trait,” says Que.

That’s not all. Consider the newer breakthrough of genome editing (GE). The advantage of this cutting-edge plant science means making no additions of transgenes to a plant's genetics. Que explains: “Think of it as delivering DNA editing machinery into cells that allow you to edit, remove or alter genes far more precisely.”

Both GM and GE are more targeted than traditional methods of breeding. But here’s the problem. Both techniques rely on delivery mechanisms, either for embedding the new gene into the target or sending the editing machinery to the right place.

Studies from experts around the world have proven that delivery is a complex problem to solve. It can be inefficient, heavily depending on the variety of soybeans. On top of that, transforming plants can be time-consuming and resource intensive.

Now, a team of experts led by Que, Heng Zhong and Changbao Li at Syngenta have made a breakthrough. A new proprietary technique called 'genotype independent fast transformation', or GiFT for short, aims to reduce soybean crop losses.

In the lab at Research Triangle Park in North Carolina. From left to right: Changbao Li, Heng Zhong and Tara Liebler.

In the lab at Research Triangle Park in North Carolina. From left to right: Changbao Li, Heng Zhong and Tara Liebler.

Syngenta Principal Scientist Heng Zhong at work in the lab.

Syngenta Principal Scientist Heng Zhong at work in the lab.

Soybeans from the GiFT trials.

Soybeans from the GiFT trials.

The GiFT method was recently published in the leading plant science journal Plant Communications.

Que says: “With other methods, it can take around 100 to 120 days to obtain transformed plants. With GiFT we can achieve this in 40 days.”

GiFT is a huge and important step forward because it works with many soybean varieties with high efficiency. Traditional genetic transformation happens with just a few cells at a time, in highly controlled lab conditions. Even better, GiFT is effective no matter the soybean variety.

“The two big problems are how long the process takes and its efficiency. Using this new method, we've managed to solve both at the same time,” says Que, with a smile.

Que points out that this kind of rapid transformation is invaluable for getting resistance to disease into the genetics of this essential crop. “We’ve been working on ASR resistance for 10 years or more,” he says.

He continues: “Immunity from just a single trait only works in one way, and that isn’t enough – do that and you’ll see the disease adapt in just a few short years.”

Rather, using the speed, high volume and genotype independence of this new technique, Que says that “we can build and test many combinations for durable resistance that works on multiple modes of action”.

This gift looks set to be a year-round present for soybean farmers who are keen to protect and preserve their crops.