Unwanted guests: the insect eating our culture

Tackling long-tailed silverfish in museums

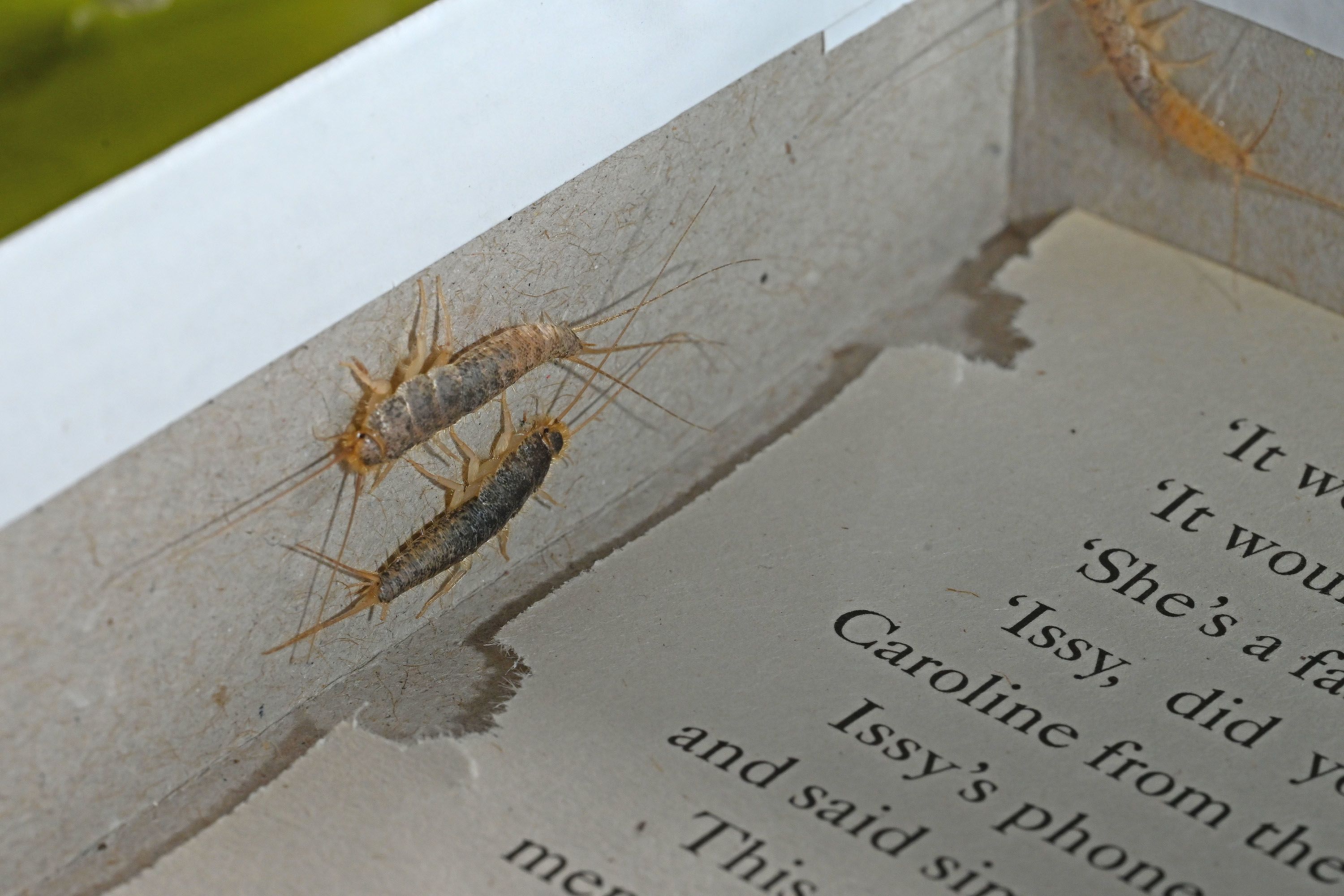

Its favourite meals include paper, books and textiles and it can live up to 10 years. Meet the long-tailed silverfish, a prehistoric pest threatening museum collections.

Native to South Africa and North America, the long-tailed silverfish is a new arrival to European shores, thought to have hitched a lift in cardboard and paper packaging. In the UK, it was first officially reported by a heritage organization in 2016, although mentions of ‘large silverfish’ in the country’s museums date back to 2011.

Its unique characteristics make the long-tailed silverfish a menace to precious artefacts.

Its unique characteristics make the long-tailed silverfish a menace to precious artefacts.

While the more common, smaller silverfish is routinely spotted in damp, domestic settings such as bathrooms and is relatively easy to tackle, the long-tailed relation, known as Ctenolepisma longicaudatum, is an altogether different beast. And it’s the insect’s unique characteristics which make it a menace to precious and priceless museum artefacts.

Sean Loakes, Technical Manager at Syngenta UK & IRE – Professional Pest Management.

Sean Loakes, Technical Manager at Syngenta UK & IRE – Professional Pest Management.

Chomping through culture

“Because they are small [to the human eye], you would think they are the same as the ordinary silverfish,” says Sean Loakes, Technical Manager at Syngenta UK & IRE – Professional Pest Management.

“That makes them challenging to identify. And the long-tailed silverfish can survive at a much lower humidity, like you have in museums, and they eat a huge range of different things. That includes most animal and tree products, so things like silk, paper, glue, and cardboard. They can digest that, and they can live a long time.”

The long-tailed silverfish’s ability to thrive at low temperatures and low humidity, and persist on collagen-rich, high-protein content, is key to its survival. It also explains why museums and their curated collections offer a smorgasbord of dishes to this member of the Zygentoma insect family, from the glue on the bindings of old books to object labels. Given that this ancient and primitive insect has been on earth for more than 200 million years, it’s had time to hone its appetite, which is voracious to say the least.

Loakes says: “What’s strange about the long-tailed silverfish is the diet. Normal silverfish would eat some of the same things, but they would never survive in normal conditions. Normal silverfish have to stay tucked away in places with high humidity - something like 70-plus percent humidity - because otherwise they would eventually die. This isn’t the case with the long-tailed silverfish. It can survive in normal, ambient conditions.”

In the past, good storage conditions with low humidity in museums have seen off the common silverfish. But this new invader, also known as the grey or paper fish, is not so easily eradicated, as museums and pest experts have discovered.

Sean Loakes, Technical Manager at Syngenta UK & IRE – Professional Pest Management.

Sean Loakes, Technical Manager at Syngenta UK & IRE – Professional Pest Management.

Chomping through culture

“Because they are small [to the human eye], you would think they are the same as the ordinary silverfish,” says Sean Loakes, Technical Manager at Syngenta UK & IRE – Professional Pest Management.

“That makes them challenging to identify. And the long-tailed silverfish can survive at a much lower humidity, like you have in museums, and they eat a huge range of different things. That includes most animal and tree products, so things like silk, paper, glue, and cardboard. They can digest that, and they can live a long time.”

The long-tailed silverfish’s ability to thrive at low temperatures and low humidity, and persist on collagen-rich, high-protein content, is key to its survival. It also explains why museums and their curated collections offer a smorgasbord of dishes to this member of the Zygentoma insect family, from the glue on the bindings of old books to object labels. Given that this ancient and primitive insect has been on earth for more than 200 million years, it’s had time to hone its appetite, which is voracious to say the least.

Loakes says: “What’s strange about the long-tailed silverfish is the diet. Normal silverfish would eat some of the same things, but they would never survive in normal conditions. Normal silverfish have to stay tucked away in places with high humidity - something like 70-plus percent humidity - because otherwise they would eventually die. This isn’t the case with the long-tailed silverfish. It can survive in normal, ambient conditions.”

In the past, good storage conditions with low humidity in museums have seen off the common silverfish. But this new invader, also known as the grey or paper fish, is not so easily eradicated, as museums and pest experts have discovered.

A new approach

Abby Moore is IPM (Integrated Pest Management) Manager at the British Museum in London. Prior to joining earlier this year, she spent 12 years at London Museum, formerly known as the Museum of London.

She says: “It was about 2015 when we first started to notice bigger silverfish in a few areas. After investigating, we found out that it was a new species of silverfish that hadn’t really been reported in the UK. The London Museum was the first [UK] museum to report it.”

London Museum spent five years trying different ways to reduce long-tailed silverfish activity throughout the building. But nothing worked effectively.

“We were seeing increasing numbers and increasing distribution around the site,” recalls Moore. “We saw damage to packing material. They seemed to really like acid-free tissue which is used very widely in museums to pack collections.

Acid-free tissue paper is used for wrapping and protecting delicate items during storage or shipping because its neutral pH prevents damage, tarnishing, and yellowing.

Only a handful of insects are able to break down the cellulose in books and paper, but silverfish have enzymes in their digestive system that allow them to receive nourishment from these items.

Moore says: “We also found damage to high-quality papers used in storage of paper-based collections. That was paper with quite a high cellulose content which was very nutritious for the silverfish. The insect was also attracted to paper materials that had some added protein or starch content too, such as items that had undergone conservation treatment where wheat starch paste or methyl cellulose adhesive had been used, as well as photography paper that had a gelatine coat.”

Around this time, Moore heard about a trial at a library in Norway which had been dealing with the same insect – a silverfish with an average length of between 10 and 15 mm and a tail and antennae both longer than its body. During the trial, a product called Advion, registered by Syngenta for cockroach control, had proved successful in dealing with long-tailed silverfish. So, Moore contacted Syngenta’s European pest management business.

As a result, a trial to target long-tailed silverfish with Advion Cockroach Gel was given the go-ahead at London Museum. This year-long initiative, which involved placing spots of Advion Gel on carpets and skirting boards in affected areas, began just before the Covid lockdown came into force in 2020 and continued during the pandemic, conducted under license by specialists i2L Research.

Only a handful of insects are able to break down the cellulose in books and paper, but silverfish have enzymes in their digestive system that allow them to receive nourishment from these items.

Only a handful of insects are able to break down the cellulose in books and paper, but silverfish have enzymes in their digestive system that allow them to receive nourishment from these items.

During the trial, Loakes was employed by i2L Research, later leaving to work for Syngenta. He recalls the work at London Museum.

“I was one of the few people driving to London on an official pass to go to the museum, which was empty because no one could go to it. I was checking the silverfish every month. Because I was there in lockdown and there were no people in, I was able to go in, and I would see the bodies of the silverfish on the floor where the [Advion] product was in use.”

The results were impressive. Within 165 days, there were 95 percent less long-tailed silverfish in treated areas than at the start of the trial. In untreated areas, there were 26 percent more long-tailed silverfish.

Moore says that the results of the trial were “fantastic”.

“After we did the trial, that was the turning point,” recalls Moore. “We noticed quite quickly the impact that it had. There was still a low level of activity, but it had brought it back down to what was acceptable and low risk.”

Two years after the trial, with no additional treatment, London Museum reported that long-tailed silverfish numbers remained significantly reduced and under control.

A widespread problem

When London Museum initially reported long-tailed silverfish on its premises, other UK heritage organizations followed suit from 2017 onwards, among them the Science Museum in London, the London Library, the Brotherton Library in Leeds, and The Stanley & Audrey Burton Art Gallery in Leeds.

Moore says: “We identified it at the London Museum first, but I’m sure it’s been present in other museums for years as well, it’s just been misidentified because it looks similar to another type of silverfish.

“As soon as we started talking about it at London Museum, a handful of museums approached me and said, ‘we think we might have this as well but we just didn’t know’. I worked with a few different organizations in London and elsewhere. They started sending me insects and, yes, it was the long-tailed silverfish. I’m sure that lots of museums have had this pest for longer than we all knew about.”

Since joining the British Museum, Moore has found the long-tailed silverfish in a number of locations within the museum, as well as damage to acid-free tissue packing material and object labels. The museum’s IPM team is currently monitoring the situation and risk-assessing so as to understand the potential scale and distribution of the long-tailed silverfish population.

Today, Advion is registered for use in tackling long-tailed silverfish in various countries, including Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Spain, Slovakia, Sweden, and Switzerland.

Regarding Advion’s use in the UK for long-tailed silverfish, it is hoped that it will be approved in 2026. The regulatory situation is fairly complex. In order to market Advion Gel as a solution for long-tailed silverfish issues in the UK, it must be added to the existing product label. That label is currently approved for tackling cockroaches. So, that means waiting for the label renewal, at which time long-tailed silverfish will hopefully be added to Advion’s permitted use.